Full stop: Intellistop’s pulsating rear lamp module caught in bureaucratic limbo

Almost any commercial vehicle already traveling America’s highways can do so with brand-new technology aboard because the U.S. regulatory structure has holes in it. But when it comes to new equipment, fresh from the factory, a simple yet effective system that adjusts the way trailer brake lights work can become mired in a bureaucratic morass.

One industry newcomer, the manufacturer of a device that pulsates rear stop lamps in an effort to reduce rear-end collisions, is learning that the hard way.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) in the last three years has granted four exemptions that allow brake-activated pulsating rear lamps on equipment already in operation with fleets. Tank truck carrier Groendyke Transport secured the first such waiver three years ago, and trash hauler Waste Management obtained the most recent one, just in January.

But a similar application for an exemption from Section 393.25(e) of FMCSA regulations, filed by Intellistop in December 2020 and published in the Federal Register last June, has yet to be approved—long after FMCSA was expected to decide; applications usually take 180 days from receipt to a decision from the agency. So, what’s the holdup with Intellistop’s application? Turns out, the delay has to do with which federal agency has jurisdiction.

According to a recent email from Jack Van Steenburg, FMCSA’s executive director and chief safety officer, FMCSA may not have the authority to grant an exemption to a manufacturer on behalf of motor carriers who voluntarily “choose” to use Intellistop’s product to reduce costly rear-end crashes. That’s because, while FMCSA regulates “in-use” operation of commercial vehicles over 10,000 lb. in interstate commerce, it’s the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) that oversees the safety of newly manufactured vehicles, equipment, and technology—as covered by a Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS).

And though the FMCSA and NHTSA missions are virtually identical—save lives by reducing crashes—they’re proceeding as if they’re on opposing sides by indefinitely idling a promising solution for the problem of rear-end collisions, which aren’t improving.

A review by Bulk Transporter suggests that FMCSA and NHTSA are too distracted by regulatory semantics—like the definitions of “manufacturer” and “make inoperative”—to focus on improving highway safety today. In short, it seems the agencies are more concerned with policing grammar than promoting common-sense safety measures supported by NHTSA’s own taxpayer-funded research.

Caught in the middle of the two U.S. Department of Transportation agencies is a woman-owned business with a means of reducing rear-end collisions that is more cost-effective and potentially safer than other methods—and it’s one that has the support of multiple trucking associations, fleets, and trailer manufacturers.

And if Intellistop’s exemption isn’t granted, the entire trucking industry should worry.

That’s because, if Van Steenburg’s email to Intellistop is correct, and FMCSA is forced to deny the exemption, the agency’s decision would be based on NHTSA’s interpretation of the words “make inoperative” in the FMVSS; and FMCSA already has granted many parts and accessories exemptions for technologies that essentially render vehicles inoperative after they’re sold—and could be bound by law to go back and undo all of them.

“You can’t go halfway in,” Intellistop president Michelle Hanby insists. “You can’t say, ‘We’re just not going to let this one happen.’ If this is really how you feel, then every manufacturer that’s been granted an exemption is probably going to be under the microscope, and that’s only taking us backward on safety.”

Vehicle standards

Today’s U.S. brake lamp standards, including the steady-burn requirement, were developed in the 1960s, during the time of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and were later standardized for motor vehicle manufacturers by the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, four years before NHTSA was created.

A review of the history of rear-lighting systems, “Historical Development and Current Effectiveness of Rear Lighting Systems,” conducted in 1999 by the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, doesn’t mention the phrase “steady burning” but points to difficulties with early electrical systems and rear lamps, including greater exposure to dirt, corrosion, and damage that reduced their effectiveness or intensity levels, as a rationale for the requirement. If the lamps weren’t staying on, it likely was due to faulty wiring or a malfunctioning light.

That’s not the case with today’s sealed LED lighting and advanced vehicle technology that supports LEDs.

The “make inoperative” standard is outlined in 49 U.S.C. section 30122, which states “a manufacturer, distributor, dealer, rental company, or motor vehicle repair business may not knowingly make inoperative any part of a device or element of design installed on or in a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment in compliance with an applicable motor vehicle safety standard … .” Thus, OEMs must make sure vehicles and equipment meet all applicable safety standards and must permanently affix a label certifying compliance. If they don’t, they’re subject to a hefty penalty for each violation—up to $22,992 per day.

But certification only guarantees a vehicle is “operative” on the date manufactured. As soon as it is used, and wear and tear incorporated, or anything is changed, including routinely replaced items like tires or windshield wipers, there’s no way to revalidate the vehicle still complies with the FMVSS. So, NHTSA and FMCSA work together to pursue compliance through mechanisms such as roadside inspections.

And though both agencies exist to promote highway safety, they do it in different ways.

Basically, NHTSA regulates the assembly of “new” motor vehicles, and FMCSA regulates the operation of “used” commercial vehicles. While NHTSA is charged with ensuring that vehicles meet pre-sale standards, FMCSA is responsible for ensuring they are properly maintained. And while the two agencies have their own regulations, some of FMCSA’s point to NHTSA’s standards, including the lighting requirements in FMVSS 108.

Thus, the two agencies are inextricably intertwined in their safety missions. But like any two family members, they don’t always agree on what is most important—as with their differing stances on the safety benefits of “pulsating” brake lamps.

Flashing lights

Barry Detlefsen, vice president of safety at San Antonio-based Coastal Transport, previously spent 40 years with the Texas Department of Public Safety Highway Patrol, specializing in commercial vehicle enforcement. He also served as a certified trainer who instructed new officers on the North American Standard Inspection Program. He’s intimately familiar with commercial vehicle standards, driver behavior—which he says is worsening due to increasing vehicle automation and, of course, cell phones—and the persistent threat of rear-end crashes.

FMCSA’s Report to Congress, the Large Truck Crash Causation Study (LTCCS), detailed the findings of a multiyear effort, jointly undertaken with NHTSA, which examined 967 crashes that included 1,127 large trucks, 959 non-truck motor vehicles, 251 fatalities, and 1,408 injuries. The study showed the largest percentage of crashes were rear-end collisions (23.1%). Additionally, NHTSA’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) indicates rear impacts accounted for 19.3% of fatal crashes (964) involving large trucks in 2019.

Among the critical reasons for crashes identified in the LTCCS, conducted from 2001 to 2003, inattention, or a lack of recognition, led to 35% of the crashes in trucks. So how do you better gain drivers’ attention, and reduce the frequency of costly rear-end collisions? Through flashing lights and movement, Detlefsen said.

“The human eye is attracted to movement and flashing lights,” he said. “That’s how we’re wired. To give an example, our traffic signals will flash at us, and that catches our attention. That’s why the Highway Department builds our lights that way. As far as movement goes, have you ever been seated in your favorite recliner, watching TV, and your focused vision is on the television set, but your peripheral vision still catches that little bug, or mouse, or fly that happens to pass by? That’s because it grabs your attention.”

Since humans are wired to notice flashing lights, they could help reduce rear-end collisions if built into brake lamps. The only problem is those two pesky words—“steady” and “burning”—in the FMVSS. “That’s where the regulations are contrary to the potential solution being offered, which is a flashing brake lamp,” Detlefsen said. “Because if that brake lamp flashes, it’s an on-and-off light, and therefore doesn’t meet the definition of steady burning.”

So, should a seemingly outdated standard remain in place, or should it potentially be revised to help improve roadway safety? NHTSA’s own research points to the latter.

Supporting research

NHTSA examined enhanced rear lighting and signaling systems for a report published in 2002 that mentioned numerous attempts to develop flashing brake systems as far back as the 1970s. But, NHTSA said, “without additional scientific research showing that a flashing lamp will be detected significantly faster than a steady-burning lamp, NHTSA will not consider altering the standard.”

Then, in 2009—nearly 13 years ago—NHTSA published its “Evaluation of Enhanced Brake Lights Using Surrogate Safety Metrics,” which acknowledged that “previous work had shown promise for reducing the number and severity of rear-end crashes” and that its current work indicated “flashing improves rated attention getting.”

In addition, according to the report, “LED experiments show that ‘wider is better.’ In other words, flashing the outboard lamps produces greater rated attention getting than other flashing arrangements.” Therefore, “in general, it can be said that flashing is beneficial in terms of rated attention getting and bright flashing of the outboard lamps are even more beneficial.” More plainly, flashing the brake lamps and additional lights, like trailer marker and clearance lights, would improve attention-getting.

In regard to static testing, the report states, “of particular interest is that while simultaneous flashing of brake lamps without an increase in brightness led to significant improvement over baseline, pairing the flashing with increased brightness significantly enhanced the eye-drawing capability, nearly tripling it compared with flashing alone.”

The conclusion was more decisive: “Steady ordinary braking levels appear to be totally ineffective in drawing the driver’s eyes to the forward view for the conditions tested in the current study. It appears therefore that there is much to be gained by flashing and increased brightness. Fortunately, adequate light output levels can be achieved with present day LED technology.”

Road testing also supported the assertion, saying “flashing with increased brightness may be effective in reducing the incidence of long offroad glances” and that “drivers exposed to the flashing with increased brightness were more likely to brake in response as compared with conventional, steady brake level signals.

“This suggests that flashing with increased brightness represents a strong cue.”

Exemption solution

Despite the evidence gathered, NHTSA has not moved to revise the standard. And the agency has a history of moving slowly in response to its own findings. A CBS news investigation recently revealed NHTSA’s own researcher said in the early 1990s that the federal standard for seat backs wasn’t sufficient to prevent deadly crash collapses, but it wasn’t updated until mandated by the infrastructure law signed last year.

So fleets, manufacturers, and the FMCSA developed and allowed their own solution.

Unlike flashing lights, which turn off and on, “pulsating” lights dim and brighten by modulating the voltage, so they maintain a “steady burn,” meeting the FMCSR standard, while creating the perception of flashing.

Groendyke was the first fleet to test amber, brake-activated, center high-mounted stop lights on its trailers as a way to reduce rear-end collisions. It’s study, conducted from 2015 to 2017, which included 632 tank trailers, revealed trailers with brake-activated pulsating lights and steady-burning brake lamps were involved in 33.7% fewer rear-end collisions than trailers with only steady-burning red lamps. Moreover, trailers with pulsating lights were involved in zero rear-end crashes at railroad crossings, where carriers hauling hazardous materials must stop in what Detlefsen calls an “abnormal event” to the average motorist.

However, Groendyke also attracted unwanted attention from law enforcement during testing, so it opted to pursue an exemption, combining its test results with NHTSA research and other evidence to make a compelling case to FMCSA, which has the authority to grant FMCSR exemptions if it determines the change “would likely achieve a level of safety equivalent to or greater than the level of safety provided by the regulation.”

According to Van Steenburg’s email, FMCSA and NHTSA officials met to discuss FMCSA’s plan to grant Groendyke’s exemption. NHTSA was hesitant to do so, but an associate administrator for NHTSA’s rulemaking division who previously worked for the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration was familiar with the challenges faced by tank truck carriers, so gave his blessing, and FMCSA moved forward. As soon as the exemption published, the agency was “bombarded” by requests from other bulk haulers for the same exception. So, to avoid granting thousands of related exemptions—National Tank Truck Carriers says there are more than 20,000 tank truck carriers in the country—NTTC gained an exemption in October 2020, clearing the way for carriers to equip red or amber brake-activated pulsating lamps on the rear of tank trailers.

Grote Industries, a lamp manufacturer, also received a pulsating brake lamp exemption in December 2020 that included van body trucks. And then, in one of her last acts as the acting FMCSA administrator, Meera Joshi signed off on Waste Management’s rear-lamp exemption covering its commercial vehicles on Jan. 20.

None of these exemptions make pulsating lamps mandatory.

They simply afford carriers the option of adding technology NHTSA’s own research indicates may help protect them from inattentive drivers who cause costly, and potentially deadly, crashes by driving into the rear of their commercial vehicles—something that’s out of their control no matter how much money they invest in safety. And carriers will take any protections they can implement given the proliferation of “nuclear verdicts.”

Granting Intellistop’s exemption would allow carriers to operate its brake-activated warning lamp module without fear of fines.

Full stop

So why hasn’t FMCSA approved the company’s exemption request?

Officially, the agency said “DOT has the exemption request under active review, and should have a decision out shortly. The Intellistop inquiry touches on both FMCSA’s and NHTSA’s authorities, however we cannot comment further at this time.” NHTSA did not respond to phone and email messages but Richard Van Iderstine, a retired NHTSA lighting standards engineer, says the agency historically has been “adamantly against” flashing brake lights on vehicles without center-mounted stop lamps because “vehicles following other vehicles might mistake the flashing brake light for a turn signal, if they can’t see both the brake lights.”

In addition, Van Steenburg’s email reveals that NHTSA would like to extend the definition of “motor vehicle manufacturer” to include a company like Intellistop, but that notion contradicts previous legal interpretations from the agency that seem to establish aftermarket manufacturers aren’t NHTSA-regulated “manufacturers.”

NHTSA voiced its concern with this provision last summer after hearing about dealers who were installing pulsating, center high-mounted stop lights on light-duty vehicles. And while FMCSA has authority over carriers, NHTSA regulates the manufacturers, so the latter agency would prefer FMCSA only grant exemptions to carriers. But FMCSA isn’t equipped to handle 20,000-plus exemption requests, which would force the agency to hire lawyers and do nothing but process exemptions to keep up with the deluge.

And the reality is many manufacturers already have secured safety-related exemptions for carriers to utilize; brake-light flashing already has been in use for many years—it’s a recommended practice by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation—steady-burn exemptions already exist for other classes of vehicles; some states, like Tennessee, already allow all classes of vehicles to use “continuously flashing light systems,” defined there as “brake light systems in which the brake lamp pulses rapidly for no more than 5 seconds when the brake is applied.” And the goal, regardless of who’s making the request, is the same: To improve highway safety by reducing crashes.

By granting exemptions, FMCSA can move safety forward faster than NHTSA, which rarely awards them to manufacturers.

“If NHTSA really needs statistics, why wouldn’t you start with the manufacturers?” Hanby said. “Make it an option code, and if a carrier is buying a trailer, and wants the option on there, it will be delivered with that option. You can saturate the market faster, and generate statistics quicker, to see if it’s going to make a change.”

Intelligent support

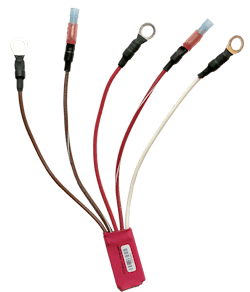

Public comments published on the Federal Register overwhelmingly support Intellistop’s exemption request, which also differs from the others in that it seeks to pulse the existing lights, rather than adding brake lamps. American Trucking Associations said it supports “the use of the Intellistop module, which pulses the preexisting brake, clearance, and I.D. lamps” for several safety-related reasons, and that “granting this exemption can provide valuable real-world experience and data” and also “inform future regulatory actions related to ERS (enhanced rear signaling) technologies.”

The Intellistop module was NTTC’s preferred solution in its study conducted with Tankstar USA, which produced positive results. When contacted by Bulk Transporter, NTTC president and CEO Ryan Streblow reiterated that, while the association doesn’t specifically support any one vendor, it continues to back any device that improves safety. And while there are other good solutions, Intellistop’s arguably is the most compelling.

It pulses more high-mounted lights, which catches the attention of more trailing drivers; it’s easy to install in a trailer’s nosebox, so it’s intrinsically safer because no drilling is needed and installers don’t have to climb on top of a tank; and it’s more cost-effective because no trailer modifications are required and fleets don’t have to down trailers as long, meaning they continue generating revenue and benefitting the supply chain, supporters contend.

“Ideally, once this becomes an accepted industry standard, or a NHTSA-approved device, our trailer manufacturers could just install this at the time of manufacturer,” Detlefsen said. “Because at this point, we’ve got to down the trailer for a short period of time in order to install the device. So wouldn’t it be nice if we could just get that done during the initial build?

“Modifying the regulation certainly makes more sense than granting multiple exemptions.”

Van Iderstine, who retired in 2003, acknowledged it might be time to revise the standard, given the advances in lighting technology since the rule was created more than 50 years ago, instead of splitting hairs over who’s allowed to install a safety device. “That’s certainly a good argument for a petition, and a comment to a petition,” he said. “And while the agency says, ‘Well, the comment periods last 60 days, or 90 days, or whatever,’ in fact, the comment period never really closes, because letters that come in as comments always get logged and entered in the docket, and the engineer working on that issue gets the comment anyway.”

Instead, it seems, NHTSA wants to put the burden of improving safety on carriers, even though they could be penalized in roadside inspections, adversely affecting their Compliance, Safety, Accountability (CSA) scores. Detlefsen said Coastal weighed the risks and made a “safety-motivated decision” to install the Intellistop module on its trailers without an exemption, and he’s already seen a decline in rear-end collisions after outfitting one-third of Coastal’s approximately 500 tank trailers. It’s not the only fleet moving forward, either.

Intellistop’s module was installed on the fully loaded United Petroleum Transports (UPT) trailer displayed during 2021 Tank Truck Week. Gemini Motor Transport, which also submitted a public comment, is utilizing the device, as are Casey’s, Rogers Cartage, and many other for-hire tank trailer and dry van carriers.

Unstoppable

Other fleets are waiting on FMCSA’s decision.

Hanby admits she didn’t think she would be in this situation when she started Intellistop in 2019, believing that “pulsating” brake lights clear the prohibition against flashing lights, and her system is in line with NHTSA’s research, in terms of the duration of pulses (four in 2 seconds), and the limit for brightness.

As far as she’s concerned, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg should be grateful for a technology solution handed him on a silver platter, considering he said during CES 2022 the federal government will pave the way for innovation in transportation by helping companies bring technology to the market. “We should plan proactively to support the growth of new ideas and make sure that Americans share the benefits,” Buttigieg said.

Yet a woman-supplied solution that is easier for everyone, including carriers, manufacturers, and FMCSA, still is languishing in bureaucratic purgatory—under an administration that says it is committed to diversity—despite all the evidence in its favor.

“I believe I’m in a turf war,” Hanby confided.

Fortunately for carriers, she isn’t one to shy away from a fight. Especially not this one.

Hanby’s mother was killed by a distracted driver on Nov. 12, 1993, while on her way to watch her daughter play basketball for Arkansas. She was 50 years old at the time—the same age as Hanby is now. Texas A&M women’s basketball coach Gary Blair, then the new coach at Arkansas, mentioned the tragedy in his memoir, “A Coaching Life,” on pages 106 and 107. That life-altering incident led Hanby and a partner to start BrakePlus, which provides owner-installed pulsating brake light modules for passenger vehicles, more than 10 years ago.

Van Steenburg’s email to Hanby indicates Intellistop’s exemption request has been elevated to a “policy decision.” If it’s ultimately denied, Hanby, who’s already reached out to congressmen in multiple states, plans to retain legal counsel, and then turn her attention to changing the regulation—and she fully expects to have the support of countless commercial motor vehicle manufacturers and carriers in her corner.

“Personally, I’m not against it—if it was for a vehicle over 80 inches (in width, like a commercial trailer),” Van Iderstine said.

And if FMCSA denies Intellistop’s exemption, it likely would force the agency to nullify numerous established parts and accessories exemptions for devices that, by the letter of the law—instead of its safety spirit—make a vehicle noncompliant with NHTSA’s FMVSS, including Ford’s exhaust system, multiple windshield-mounted camera systems, and Stoneridge’s Mirror Eye, which actually replaces the mandated rear-vision side mirrors with cameras.

“I’m not giving up,” Hanby vowed. “I’ll sink my teeth into it.

“I’m asking for an exemption now, but if it’s not granted, then I’ll turn my attention toward actually changing the regulation. But why is that up to me? I am nobody. It’s common sense, and it needs to be done.”