How to prepare for an OSHA tank-cleaning inspection

The U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) now is scrutinizing tank-cleaning operations across 11 states in an effort to make the job safer for workers in the industry.

OSHA initiated the endeavor in August with the concurrent establishment of Regional Emphasis Programs (REPs) in Regions V and VI that target the transportation tank cleaning industry. Following a three-month period of outreach, randomized inspections of covered establishments began in late October.

They will continue for the foreseeable future.

The Region VI program officially expires in July 2024, but the Region V program extends through July 2026—and both are renewable.

“As long as there are fatalities happening, and serious injuries happening, we’ll continue the program,” said Stephen Boyd, OSHA’s deputy regional administrator for Region VI.

To help prepare tank wash operators for the unannounced inspections, Boyd spoke to attendees at National Tank Truck Carriers’ 2021 Tank Truck Week in Dallas, Texas, about the new initiative, detailing who is covered, and the primary OSHA regulations that Certified Safety and Health Officials (CSHOs) will examine while they’re on location: Permit-required confined spaces (29 CFR, part 1910.146), respiratory protection (1910.134), hazard communication (1910.1200), and personal protective equipment (1910.132).

NTTC also hosted a webinar in October featuring Aaron Gelb, an OSHA expert with the Conn Maciel Carey law firm, who reviewed inspection processes, employer rights, most commonly cited violations under each key standard—and the importance of preparing for an OSHA visit before the inspector arrives.

“If you don’t have a plan, and haven’t thought about what you’re going to do when OSHA shows up, and taken steps to prepare, the inspection almost never is going to go as well, because it’s hard to pull things together when OSHA’s waiting in a conference room, or has started talking to members of management,” Gelb said.

What’s happening?

According to OSHA, workers employed in the transportation tank-cleaning industry face many hazards that can lead to serious injury, illness, and death, including fires, explosions, hazardous atmospheres, and hazardous chemicals, rendering workers incapacitated and unable to self-rescue from the interior of a tank. The intent of the REPs is to encourage employers to take steps to address hazards, ensure facilities are evaluated to determine if the employer is complying with all relevant OSHA requirements, and to help employers correct hazards, thereby reducing potential injuries, illnesses, and death for their workers.

OSHA included grim tank-cleaning statistics in its REP announcements last summer.

Further, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System, Version 2.01, reveals “tanker-truck interiors and confined spaces on vehicles” experienced 65 fatal occupational injuries from 2011 to 2018. The leading cause of death, in both spaces, was inhalation of a harmful substance, accounting for a combined 36 instances.

The REPs, then, were established to support OSHA Performance Objective 2.1: “Secure safe and healthful working conditions for America’s workers.” These programmed inspections are separate from, and in addition to, any complaint- or fatality-based inspections. However, locations that have had a comprehensive inspection with the past three years will not receive an inspection under this program, Boyd said.

“If you’re on the list, because you’re within the industry, and OSHA shows up and says, ‘We’re here to do an inspection because of an employee complaint,’ it’s not going to stop because you had a comprehensive inspection three years ago,” Boyd said. “We’re there to investigate that complaint, and that will still continue, even though it may address hazards or conditions specific to this emphasis program.”

Who’s covered?

Region V includes Illinois, Ohio, and Wisconsin, and worksites under federal jurisdiction in state-plan states Indiana, Michigan, and Minnesota. Region VI includes Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, and federal sites in New Mexico. But state-plan workplaces often adopt federal programs, and at least one tank wash expert predicted during Tank Truck Week that these REPs eventually would become National Emphasis Programs.

Industries covered are based on the self-selected categories in OSHA’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). The categories covered by the tank-cleaning REPs are: General freight trucking, local (484110), support activities for rail transportation (488210), other support activities for road transportation (488490), freight transportation arrangement (488510), remediation services (562910), materials recovery facilities (562920), and all other miscellaneous waste management services (562998).

“This program is a partial inspection,” Boyd said. “So it’s not wall-to-wall. It’s not a comprehensive inspection. It’s limited to tank-cleaning operations and activities associated with the tank-cleaning operation. So inspectors should not be walking throughout your facility. Or if you have a sister facility that has nothing to do with tank cleaning, they should not be over in that area looking at operations within that facility.”

The critical components covered by the program include permit-required confined spaces (confined spaces with an associated hazard that require permits for entry), respiratory protection, HazCom, and PPE, but CSHOs also may review other hazards, including noise (1910.95), chemical (subparts H, Z), thermal (subpart I, PPE), electrical (subpart S), and fall and struck-by (subpart D) hazards, and any hazards in “plain view.” “This emphasis program gives OSHA a license to enter your facility, and once they do that, all bets are off, as far as their efforts to expand the scope of that inspection and look into other areas,” Gelb cautioned.

Permit-required confined spaces

Gelb compiled top-five lists for the most commonly violated regulations under each of the four key standards covered by OSHA’s tank-cleaning REPs. The top five for permit-required confined spaces were failures to inform employees or post signs, with 42 violations in the previous 12 months (through October 2021); evaluate the workplace (35), develop a written program (30), prepare a permit before entering (28), and test tank conditions prior to entry (19).

“Not informing employees of permitted spaces is frequently cited because it’s something that tends to be overlooked,” Gelb said. “So if you know you have spaces that require permits to enter them, make sure you have a mechanism in place to train employees, so they know and recognize what those spaces are.

“Obviously, one of the easiest ways to do that is to post signage. But signs get painted over, or get damaged and fall off, so make sure you’re tracking that.”

OSHA said inspectors will look at controls in place to eliminate or minimize confined-space entry hazards, including atmosphere-detection and other safety-related equipment on hand, and emergency rescue preparedness. “Remember, if you use an outside entity, they have to know that’s your intention,” Boyd said. “So if you’re going to say, ‘I’m going to use the fire department,’ you better have communicated with them ahead of time to make sure they have the equipment and training to provide that type of rescue.”

Training, for rescue workers, employees, and contractors, is critical. Boyd said confined-space entry permits should be kept for a year, and Gelb indicated the best proof of an effective written program is a fully updated batch of cancelled permits that match the dates employees say the entered the tank during interviews. If permits are handled correctly, OSHA can infer the employer’s processes are working, too, Gelb suggested.

Respiratory protection

The top five most commonly violated parts of the respiratory protection standard were for medical evaluations (533), written programs (371), initial and annual fit testing (298), qualitative or quantitative fit testing (157), and failure to provide Appendix D for voluntary use (154).

Inspectors will evaluate the employer’s respirator selections, Boyd said, attempt to determine if employees have had a correctly documented medical evaluation—which should include an examination in gear—and make sure masks fit snugly, employees know how to use the equipment, and it’s well-maintained. “Make sure you use (respirators),” Boyd said. “Have them hanging up where employees are working, or in their toolbox, so it’s actually helping them when they’re going in the confined spaces.”

Hazard communication

The top five most commonly violated sections of the hazard communication standard involved deficiencies in implementing and maintaining a written program (1,053), providing information and training for specific chemicals or categories of hazards (822), maintaining Safety Data Sheets (372), having Safety Data Sheets (SDSs) for each chemical in use (244), and labeling containers in the workplace (145).

“Make sure you’ve got a program, and make sure it’s up to date,” Gelb said. “If you download something, or use a generic program, it’s better than not having anything, but hopefully you work with your safety team or a safety consultant to develop a program tailored to your worksite.”

The most critical communication employees must receive details chemicals used or cleaned within the facility, how they enter the body, and their associated hazards, Boyd said. Digital SDSs are acceptable, but they must be readily available when needed. They can’t be password-protected or difficult to locate in an emergency. “Do an inventory of the chemicals you have at your site, keep an index of it, cross reference that index against the Safety Data Sheets, and make sure you’ve got all the Safety Data Sheets,” Gelb advised.

“That’s a very easy citation to avoid if you do your homework.”

Personal protective equipment

The most common PPE violations were related to certifying completion of an assessment (246); assessing the workplace to determine if PPE is or isn’t needed (188); ensuring that it’s provided, used, and maintained; selecting and having affected employees use the equipment (87); and PPE training (56). Gelb noted the data showed many employers completed the assessment but never documented the results.

“That means they’re able to offer testimony or evidence that somebody did go around the facility, evaluate operations, and provide PPE, so clearly they did the assessment, but they’re getting cited just because they didn’t document it,” he said. “That’s particularly frustrating because it’s a paperwork citation.”

Employers who aren’t certain what type of PPE they need inside their facility can contact their local OSHA office, or use a consulting service like The Occupational Safety and Health Consultation (OSHCON) program provided to private Texas employers through the Texas Department of Insurance Division of Workers’ Compensation. “If you’re not sure, make sure you ask, because buying the wrong thing is just a waste of money,” Boyd said.

Why care?

All companies have a moral obligation to protect their employees in the workplace. But for those employers who aren’t taking safety seriously, OSHA has others means of compelling compliance—both financial and reputational.

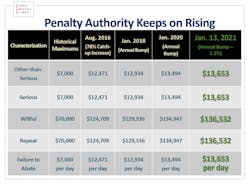

Gelb said statistics show that more than 70% of OSHA inspections result in one or more serious citations, which are increasingly costly. The max penalty for other-than-serious and serious violations was $7,000 for many years. That fine jumped to $12,471 per citation in 2016, and has increased annually since. Willful and repeat violations went from $70,000 to $124,709 in 2016—and had reached $136,532 as of January 2021. Employers also now can be fined almost $14,000 per day for failure-to-abate violations.

Furthermore, the number of repeat violations has doubled, going from 2.4% of the total violations issued by OHSA in 2002 to 5.3% in 2020. That’s particularly bad news for employers covered by these tank-cleaning REPs, which include two of the top-five most frequently cited violations in 2021, No. 2 respiratory protection and No. 5 hazard communication, standards for which CSHOs are “likely going to find some deficient element of your program” unless its thoroughly vetted ahead of time, Gelb said. And when employers are fined for frequently cited standards, their risk of receiving repeat citations increases.

Still not convinced? Shame on you. “Even as OSHA has increased the penalty structure, there is a perception in the agency that a $250,000 citation still may not always be enough to move the needle with employers,” Gelb said. “So how do you exert greater pressure on the regulated community to get them to comply?

“One way is to essentially pull their reputation into the mix.”

Under the current administration, press releases are issued quickly, they’re heavily publicized, their more emotionally charged—and they’re not retracted, even when citations are successfully challenged.

What now?

Know your rights, your employees’ rights, and the rights granted to OSHA by these REPs, and make sure employees are equally educated.

“If your thinking is, ‘Well I’m going to refuse entry,’ OSHA can then just go to a judge and say, ‘We have an emphasis program, and this employer is covered under the emphasis program by virtue of their NAICS code,’ and they will be granted entry into your facility,” Gelb said, adding they likely won’t be as amicable upon return.

Inspections should start with an opening conference in which the ground rules are established. Employers are allowed to protect trade secrets, accompany CSHOs at all times, and participate in management interviews. OSHA can talk to hourly employees in private, but conversations on the shop floor should last no more than five minutes, Gelb advised, and any disruptions or requests should be “reasonable.”

Inspectors will ask for OSHA 300 logs and 300A forms, and any first aid and/or nursing logs, so have those handy. It’s also a good idea to identify the inspection team beforehand, including who will serve as the employer’s primary spokesman, who will escort inspectors through the facility, and who will manage documents.

Gelb’s advice for preparation includes reviewing key written programs, re-training employees or refreshing their knowledge, retaining a safety consultant if there are any questions or concerns about the process, and considering who will provide legal counsel if OSHA finds a problem during the inspection.

“If the compliance officer points out something lacking or defective, go ahead and fix it or update it,” Gelb said. “Don’t admit, ‘Yeah, you’re right, that’s a violation.’ Just say, ‘OK, we’ll address that.’ You can gain a lot of good will by doing that.”

About the Author

Jason McDaniel

Jason McDaniel, based in the Houston TX area, has more than 20 years of experience as an award-winning journalist. He spent 15 writing and editing for daily newspapers, including the Houston Chronicle, and began covering the commercial vehicle industry in 2018. He was named editor of Bulk Transporter and Refrigerated Transporter magazines in July 2020.